How did your family watch the game?

Sports were a large part of my family when I was growing up. As a small boy, my earliest memory is of my grandfather, God rest his soul, taking my younger brother (or was it brothers? The memory fades over time) to a Twins game – Bat Day at old Metropolitan Stadium in Bloomington, as the memory was enhanced for me by my grandmother and mother over the years. I seem to recall it as mother’s day, though that, too, may not be accurate. Regardless, it’s there – the ringing of the wooden bats on the metal seats and bleachers; the overhang from the upper deck down the left field line; the sun (the sun! Glorious outdoor baseball!) cresting over the upper deck, the shadows receding from the infield as the pre-game warm-ups came to a close.

I have but that one precious memory of baseball with my Grampa. It wasn’t for a lack of love for the game – I am the owner of two balls, now well over sixty years old, that bear testament to a game played between U.S. servicemen in 1944, in which my grandfather’s company lost a game played as a way to pass time during their preparation for the Normandy landing. One ball shows that Captain Ballard’s team was shut out, losing 6-0. The other bears the signature of every man that wore a glove that day.

As I said, we lacked no passion for the game. But life is cruel, and men of his vintage were stubborn; stubbornness and pride and the desire to not call attention to himself allowed glaucoma to take his eyesight in the very early 1970s. I believe I was nearing five years old at the time. Grandfather and grandsons would not set foot in a sporting arena together again during his lifetime.

His passion for the games, however, never ceased. As a former telegraph and radio operator, he reveled in the voices crackling over the air. He never went anywhere without a radio. An earpiece was seldom necessary. As my brothers and I aged, we would gladly eschew our music for his preferred talk stations; our “noise”, as he always called it, could always wait for him. And when a local team was on the air, there he was, beside the radio. Even when the game was on television, we would turn the TV sound off and turn up the radio call, long before it became a fashionable practice to do so. For the truth of the matter is this: while television announcers talk over the game, and discuss things that bring little value, the voices on the radio showed you the game.

His passion for the games, however, never ceased. As a former telegraph and radio operator, he reveled in the voices crackling over the air. He never went anywhere without a radio. An earpiece was seldom necessary. As my brothers and I aged, we would gladly eschew our music for his preferred talk stations; our “noise”, as he always called it, could always wait for him. And when a local team was on the air, there he was, beside the radio. Even when the game was on television, we would turn the TV sound off and turn up the radio call, long before it became a fashionable practice to do so. For the truth of the matter is this: while television announcers talk over the game, and discuss things that bring little value, the voices on the radio showed you the game.

I still cherish the hours spent as a small boy, outfitting G.I. Joe from the stiff cloth and plastic accessories in the small wooden locker, while the voices called the game in his room, for both our eyes. The voices echo in my mind as easily as their names roll off my tongue: Ray Christenson, the silver-tongued precisionist, telling him who, where, how, on both the Gopher gridiron and the raised basketball floor of Williams’ Arena. Al Shaver, the only voice of the North Stars and the only voice I will ever associate with professional hockey, bringing you all the action “and all the fights”, a phrase Mr. Shaver coined one hot and memorable May night against the rival Blackhawks during my impressionable youth. The voices of the Vikings varied over time, although Grampa took favor with Grady Alderman as an analyst but had little love for the men who did the call, especially Ray Scott. It was a distinction I never really understood, but one that I believe had something to do with a conflict Scott had with Bud Grant before I was old enough to remember it.

The voices did not stop when the games ended. Paul Harvey was a personal favorite of my grandfather. His practicality and common sense and rhythmic and predictable approach to his broadcast – which I can still identify and count on during the random shows I catch now and then, as an adult – were likely comforting to a man who relied on the furniture always being in the same place. Sid Hartman gave him his Sports Hero every afternoon for years, until he gave up the format, and greeted every Sunday morning when we opened the his back door for our weekly dinner at Grandma and Grampa’s. Soucheray and Reusse drove him to near anger almost daily. And, in later years, Barbara Carlson and Jesse Ventura would lead him to utter exasperation. And, of course, there was Steve Cannon, the deep voice that would lead up to the pre-game show, where the voice I will always measure against every other would ring in my ears for six months out of the year.

“Hello, everybody…”

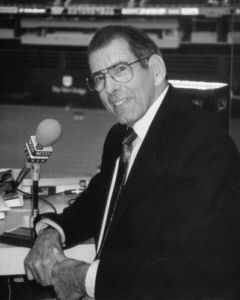

Baseball was the passion; baseball was the daily friend. The man who would later be christened the Voice of the Minnesota Twins, Herb Carneal, was that voice.

Baseball was the passion; baseball was the daily friend. The man who would later be christened the Voice of the Minnesota Twins, Herb Carneal, was that voice.

Herb Carneal shared the booth on the day the former Washington Senators played their first game as Twins in 1961, seven-plus years before I was born, and shared that microphone until this morning, April 1, 2007. It’s a cruel April Fool’s joke that the voice that has kept me company for nearly all of my 40 years is now silent, and has not been adequately replaced.

The call was the thing. He was my grandfather’s eyes. And Carneal’s call, which placed him in my lifetime but not my grandfather’s, in the hall of fame, was always precise. “Two and two now to Hoskin Powell; here’s the wind, and the pitch…” Every pitch mattered, no matter how far ahead or behind, no matter the month or the day or the weather or the man sitting next to him in the booth.

He would tell stories, of course, and so would his partners. Frank Quillici would wax on his teammates from the 60s, and the players he managed thereafter in his employ with the Twins. Joe Angel would “wave them bye-bye” for a few years. And John Gordon, former partner and current full-time play-by-play voice, would add his comments, and in the later years, when Herb’s strength began to falter, would throw in the mandatory sponsor spots and keep you up on the out-of-town scoreboard. But always, the commentary would cease for Herb’s call: “Full count now to Lenny Faedo with two outs, and the runners will go…”

Herb had a consistency about him; in the lean years, and there were many, he would sometimes let the silence between pitches fill the spaces, letting the murmurings of the sparse Met Stadium crowds drone like mosquitoes in the late Minnesota evening air. In the good years, he never broke pace. The deafening roar of the crowd when the Twins defied logic and won it all in 1987 spoke the volumes that Herb would never attempt to after his obligatory “The World Champion Minnesota Twins!”

The voices of my youth are going silent; of course, they must, as time does not stand still, and I approach middle age. After the North Stars left Minnesota, Al Shaver broadcast Gopher hockey for a few years, but retired before the Wild ever saw the light of day. Ray Christensen retired from Gophers broadcasts after 50 years in the booth. Bob Casey, the only Twins baseball stadium announcer I had ever known, fell silent two years ago, just before the season opener. And now, Herb is gone. All gone, but never forgotten by me, all still echoing in my mind.

“So long, everybody…”